I talked to my friend the other day, he currently works in academia. We talked about his satisfaction with the job. He loves it but is overworking so much that I feel that he pays a toll – stressing out, feeling obliged to work on Christmas Eve etc. I mentioned to him that it would be a good idea to reflect on this situation and prepare an exit plan (not necessarily to execute it!).

I’d like to write down what I mean by exit plan and lay out some advice on going through difficulties in your life based on my past experience. I remember giving a similar advice to a colleague some time back and I believe it’s pretty universal and not only limited to academia or even to work domain in general.

The below applies to situations when you are upset with work, but some reflection on these points may be useful even when everything goes fine.

Reflect on the reasons of your difficulties

It can be anything ranging from your own behavior to toxic environment to lack of funds, lack of ownership, mismatch between the field and your interests etc. It’s hard to settle on some specific one reason because usually it’s a combination, so don’t expect the exact once and for all cemented result from it. Yet this reflection is a good exercise that helps admitting the issue and setting yourself on a right track of solving it.

I’ll give an example from my life: there was a point when I reflected on my path in academia and had come to a conclusion that I really loved to study physics, to learn the underlying theories and progress in experiments, but that I was less interested in making scientific research than I thought I would be. Turned out that I find more satisfaction in building software because it gives me faster gratification of having something created from nothing.

Realize your limits and estimate your capacity to endure difficulties

Estimating your capacity to endure tribulations isn’t quite easy or precise since difficulties may have a compound effect and your ability to go through it is hardly a quantifiable value, but it’s still useful to project your current circumstances into some time in the future and imagine how you’d feel. This will give you an estimate on the time you can allocate to make changes.

Remember that your capabilities are limited (despite what some motivational slogans may tell you). The psyche – like muscles – can only lift a certain weight and can crack when overloaded. In practical terms it means that continuous stress/overwork over some limit (individual for everyone) will lead to nervous breakdown, depression and even physical health problems. Recovering from these conditions is much harder than avoiding it. The myth about the almighty non-stop working people - Erdős, Musk etc - is mostly a myth because it represents these people with a simplified one-dimensional snapshot. These people exist but in single digits and little is known about their happiness and mental state.

personal limits and time slot to make changes

personal limits and time slot to make changes

To me the realization of my limits came around the time of my internship in 2010. The internship was in fact a 50hrs/week software engineering job with flexible hours, and I also tried to squeeze scientific research and software engineering courses there. I ended up working 12 hours/day most days, on top of it I had 2+ hour daily commute and then my day and night continued with running theoretical physics calculations. There was a lot I learned about my limits during this time. For example, I realized that screwing up my sleep schedule on Monday will screw up the rest of the week, that brain has limited focus power – focusing too much in one area will block your ability to focus elsewhere.

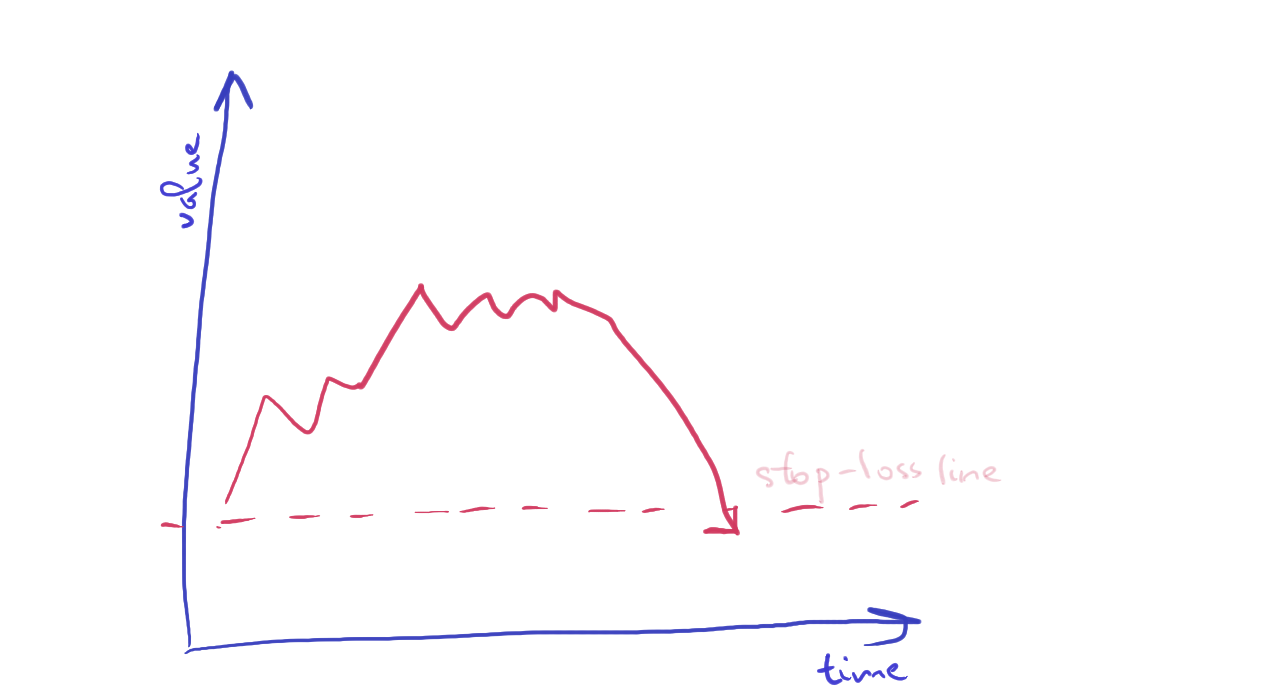

Define criteria of success and set a stop-loss signal

My first full time software engineering job was in finance, hence some concepts that I picked from there. Making an exit is a hard decision and it’s a common fallacy to continue trading when losses grow – hoping that stock prices will bounce back in your favor. A stop-loss signal is the condition set by a trader defining when losses became large enough to close the current position and exit the game.

Outside of stock market this is still a useful concept. It’s necessary to define criteria for success and failure in whatever you do. It’s also useful to define criteria when failure becomes big enough to stop doing what you’re doing and try different approach/change field etc.

stop-loss signal

stop-loss signal

My example is the relocation to the US and starting a grad school here. When setting up success/failure criteria I tried to account for both objective factors and how I’d feel about them. I understood for instance that to feel successful and accomplished in physics I’d need to perform better (have more articles, be more involved in research) than required for average PhD defense. So my criteria for success was to finish all grad level courses and publish at least 1 paper by the end of the 1st year. I decided to review my progress in the end of the 1st year – and to exit the field if I don’t feel enough progress (stop-loss). I didn’t meet all of the criteria that I’ve set upon myself, and didn’t exactly follow my stop-loss signal, instead I extended this self-probation period for 1 more year. I didn’t feel enough progress to satisfy my feel of accomplishment by this time either, and this is when I made a final decision to exit the field.

Here I’d like to thank my advisor Craig Group – thanks to him I had an opportunity to defend MSc thesis instead of the originally planned PhD, so the 2.5 year effort brought some fruit.

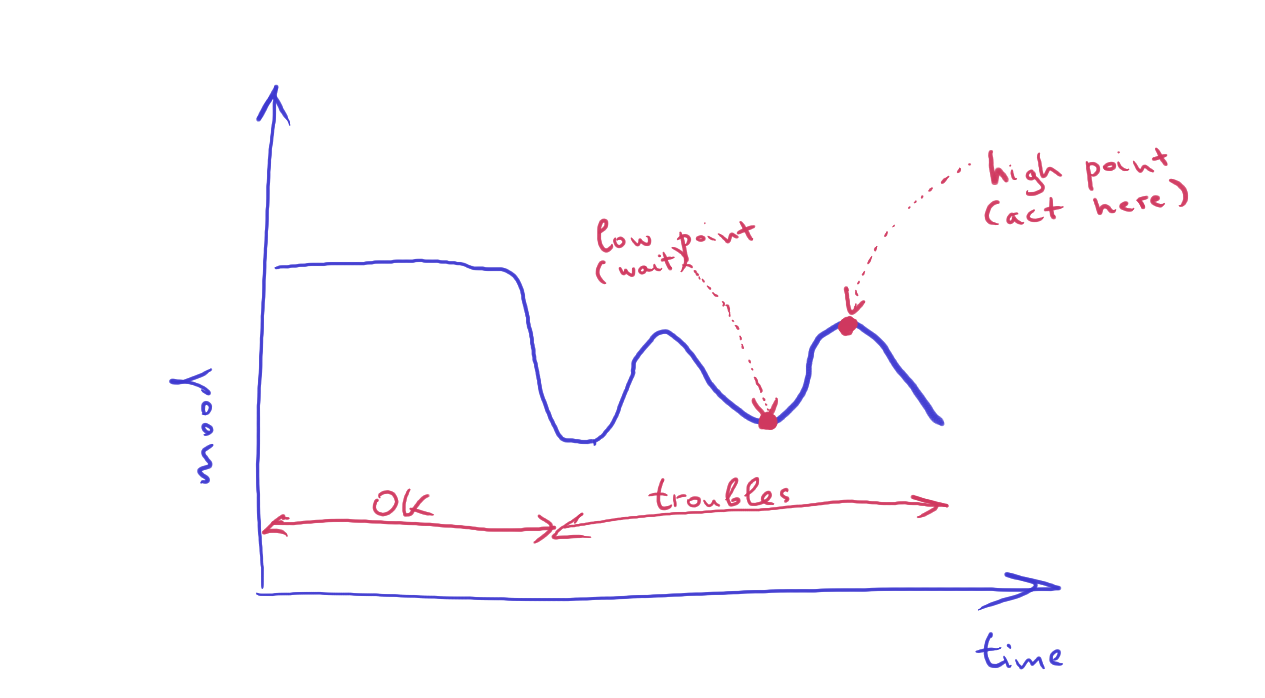

Don’t act from your low point

Tolstoy said (well, almost) that happy people are alike; unhappy ones feel satisfaction and dissatisfaction unevenly – they usually come in cycles. Once you face some troubles in work or life in general, your mood starts bouncing up and down in a wave-like fashion. Our low points – when we are dissatisfied the most – are usually the most calling times. One may feel the urge to cut ties, act harshly and swiftly. It’s almost never a good idea. Better idea would be to wait until the mood will climb back again (hours/days) and then make any actions about the situation. The flip side of this rule is the need to acknowledge problems even when the mood is in its high state.

high and low points

high and low points

Let me bring an example from my experience. Once there was an upcoming project that my team was probably going to be involved in, and I knew little about it. There was some activity happening between the manager and some folks from my team, and my lack of involvement frustrated me. After a couple of weeks our manager had shed some light on the upcoming project, and I felt both satisfaction of knowing what was going on and yet a frustration because I felt left out for the past couple of weeks. That was a low point, so I decided to let my mood settle and to find the right verbiage before talking to the manager. The words I came up with are surprisingly simple: ‘Thanks for announcing the news on the new project, I like the fact that it became more transparent now since I felt that I’m missing a part of that discussion’. They both express my concerns and reinforce the positive change.

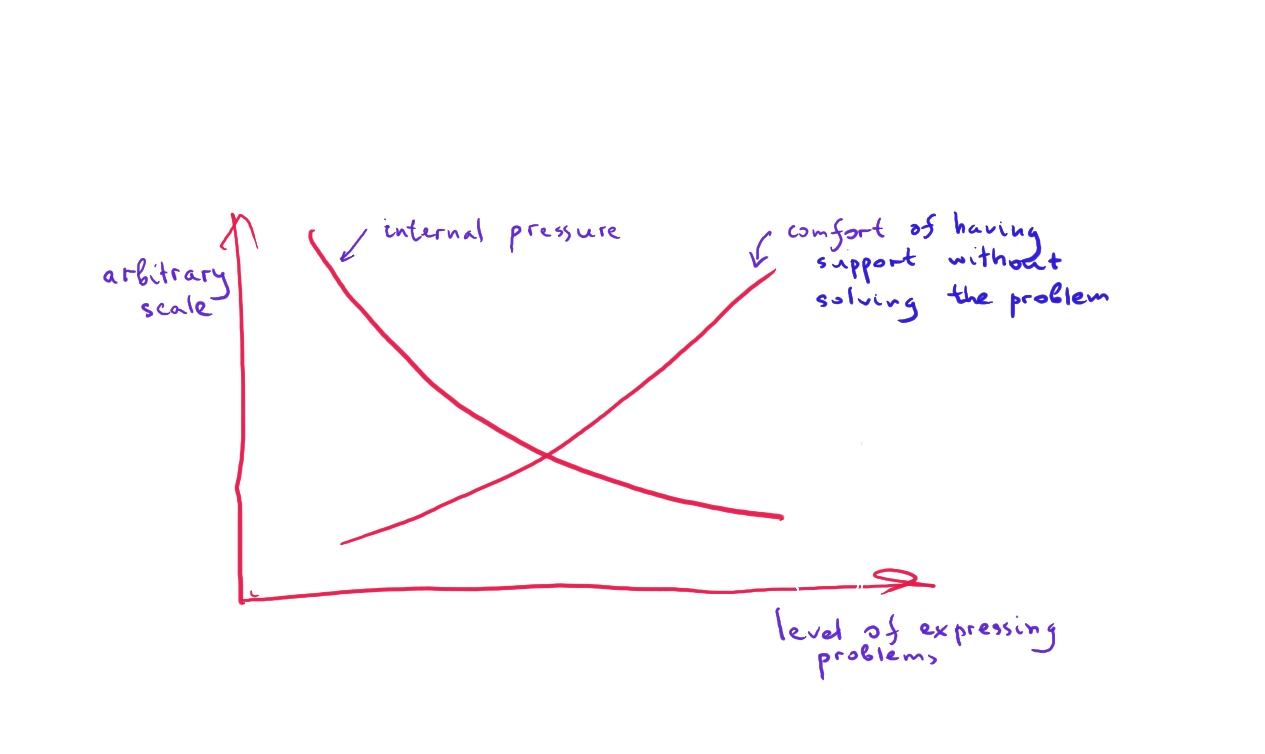

Venting frustration is a double-edged sword

Vent your frustration and seek for compassion, but do so judiciously. Remember that it is a double-edged sword.

Support from friends and family is important, but be aware that releasing too much steam is locking you into a self-pity bubble. I saw examples of both extremes: people who keep all in themselves and suffering from not being understood and people who rant about their troubles and becoming dependent on other people’s support (the latter is quite common in academia). It is important to avoid both extremes and keep the balance.

level of expressing problems and the danger of self-pity bubble

level of expressing problems and the danger of self-pity bubble

Create actionable items

This one is straightforward: you need to think about concrete actions towards resolving the problematic situation. Plan to talk to your colleagues, your advisor, your manager, think about the best time to reach them and what to tell them, look for examples of how others overcame similar problems.

In conclusion

These points are more a guidelines rather than firm rules. Even the examples I put show that I didn’t follow all of them strictly. The main point is that it’s useful to reflect on difficult situations and approach them knowing your own strengths and limits.