(Image: link)

Data aggregators

(I will use aggregation and orchestration interchangeable even though the they will normally mean different approaches - what I called aggregation with cache and aggregation with routing)

Every now and then the big organization comes with the need of unifying data fetch from multiple systems - hence building the data aggregator. Aggregation is such an attractive idea that sometimes it comes without a need - just because we, humans, love it. If we lived in the machine-dominated world, we’d probably not need any aggregation at all, or it would be built much differently. Here I’d like to describe few approaches to data aggregation and the elements of human nature that affect their designs.

This essay mostly applies to big organizations comprised of multiple subsystems - because I mostly dealt with this type of organizations. However, it will apply to smaller systems, difference will be that bigger systems would smoother out exceptions (for instance, a strong influence of individuals) while smaller will not.

Also, in this essay I deliberately don’t specify the technology selected for data aggregation: data can be stored in various DBs, served through GraphQL or REST or gRPC. I’d like to concentrate on architectural/organizational challenges that comes with aggregation rather than details of the chosen technology.

Types of data aggregation

First, the problem statement: imagine that your company has a number of systems that hold some specific data. You would like to build a way to fetch data from client applications (internal or external).

There are a few types of aggregation that I know:

- lump model - stable state

- no aggregation

- aggregation through references

- aggregation through routing

- aggregation through cache

(add note about not using app-facing backend as data aggregator for other apps)

Lump model

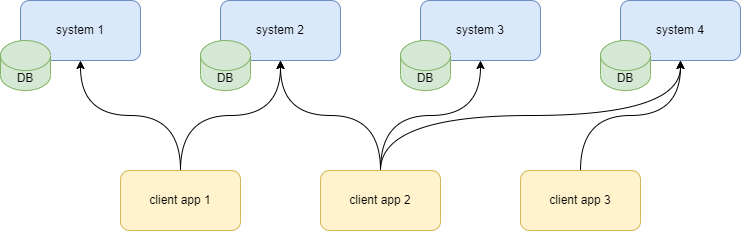

The company may decide to not build data aggregators, and in theory the app interaction will look like this: each client application connects to respective data source and fetches the needed data. The responsibility of keeping the contract is on each client application separately.

This model however doesn’t depict the ground (most stable) state of the system. In fact, the organization will require efforts to keep it like this. The true stable state will evolve from this system naturally: some teams will decide to build a cache, others will introduce a small orchestration service that will be reused by other apps thinking that this the real source of truth. Many decisions like this will be temporary, some will cement over time. In time the system will evolve into the lump model:

In fact, all the other types of aggregation also gravitate to the lump model - as entropy of the system grows and the structure of the system erodes.

The lump model has its pros and cons. One of the good things about it is limiting the blast radius: some orchestrators that are created ad-hoc may fail, but it likely won’t crash the whole system. Another benefit is being the stable state - thus minimizing the need for architectural efforts.

That said, it’s chaotic nature makes it difficult to create a map of sources. This in turn complicates resolving issues and getting the true information (you may get a cached data that may be outdated).

No aggregation

Getting back to the idea of keeping the system without aggregators. Since this is not a ground state, keeping it will need an architectural oversight. This will include supporting applications, so that they know the right sources of data, and blocking the emergence of ad-hoc aggregators.

With this model you won’t need a separate runtime for aggregation service, so no resources will be spent on it. It will require each client applications to connect to sources separately - thus replication of effort and potentially replication of errors. Changes in contracts also need to be tracked by each application separately.

This model also needs some form of book-keeping to know the sources. It can be done via comprehensive documentation or through some dedicated group of people to keep this knowledge.

The biggest problem is that the model’s integrity relies completely on conventions - agreement between architects/leadership and the teams to not build a common aggregation layer. It’s organizationally unstable.

Aggregation with references

The no-aggregation model can theoretically be enhanced by automating the book-keeping of source metadata, so it can be fetched dynamically by clients. Fetching the data becomes a 2-step process: clients would get the connection details to the source from orchestrator (discovery call), then connect to source from client side.

The challenging part of this approach is providing the source connection details that would work for all client applications. The aggregation service doesn’t control the client application deployments. So the source that is reachable from one client application can be blocked from another.

Using the discovery call is another convention that needs to be followed by client applications, so this approach is prone to erosion of conventions.

Aggregation with routing

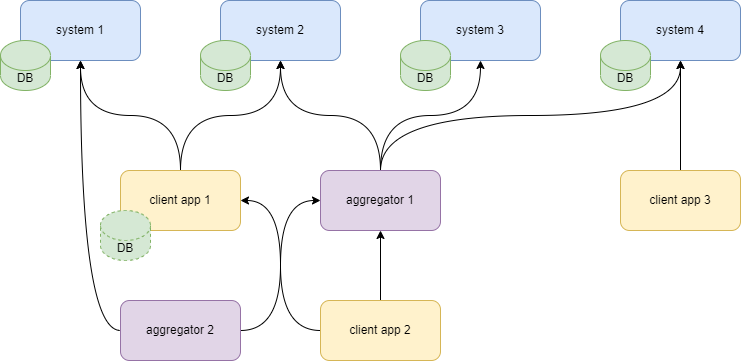

In this model the aggregator is routing the client’s request to respective source.

The convention now is that client applications will use this aggregator instead of connecting to sources on their own. Another convention is that there will be no other aggregator in the system that would connect to same sources. Not following these conventions will reduce the value of the aggregator.

Since the aggregator service now connects to sources on its own, it will need to take some responsibilities that client applications would have otherwise. It will include bookkeeping of source metadata, providing the visibility into routing details (route execution plan, latencies, datacenter hops etc), providing metrics for routes.

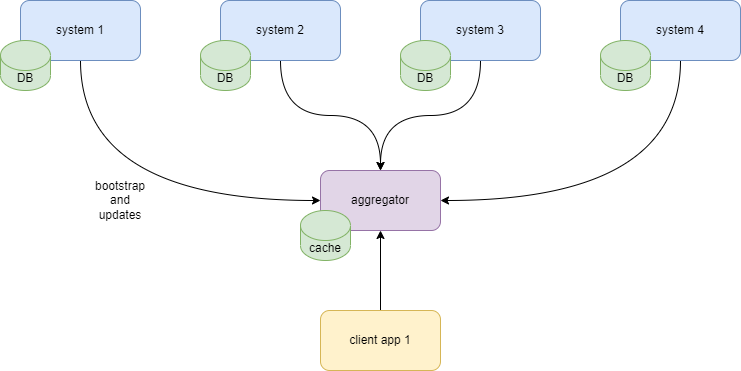

Aggregation with cache

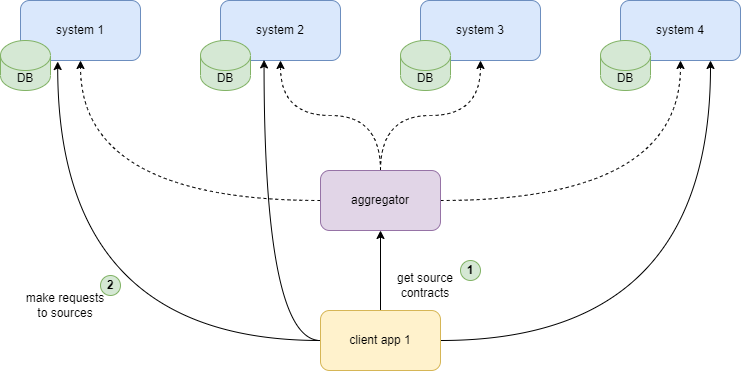

In this model the data from multiple sources is collected into the centralized cache. Clients receive data from the cache instead of actual sources.

Architecturally this model is prone to mismatches between the cache and the source, but organizationally it’s surprisingly stable! This aggregation type will likely have better chances to get additional resources/funding/organizational support than other types of aggregation. The reason behind it is the presence of data that adds weight to this type of aggregators. When some team will look for data, the aggregator will be the final stop.

note the reversed arrows between aggregator and sources

note the reversed arrows between aggregator and sources

This model lowers the dependency of sources on client read patterns since data is now served from cache. At the same time the dependency of an aggregator on client read patterns is higher: the storage needs to be efficient for client needs. It increases technical complexity of the aggregator: complexity of storing data, complexity of keeping data up to date with sources.

Apart from complexity, this model also adds the infrastructure costs due to added storage at the aggregator side.

Summary

Motivation of building the aggregator

Some may think that the main motivation to build orchestration layer is to make it ‘easier’ for applications to fetch data from a variety of sources. In fact, this motivation is a misdirection: building an orchestration layer will take more effort for an organization than connecting to individual sources (also, check out this note on complexity). The real motivation should be:

- unified model of data in the organization

- unified registry of data sources

- unified implementation of connections to sources + resiliency of this connection

- single point of tracking the changing contracts

- etc

All this comes at a price: orchestration layer is hard to build and maintain. Side note: in fact, almost all development that starts with the motivation to make something easier is a misdirection in my experience.

When to not build a data aggregator

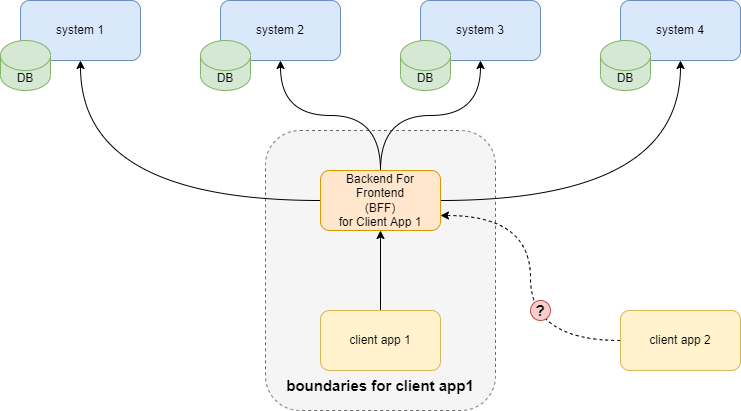

Given all the responsibilities that an aggregator needs to have, there are cases when it’s better to not have it. One example is the idea of turning the Backend For Frontend (BFF) service into an aggregator used by other services.

The BFF pattern is very useful. In fact, I’m yet to see a user-facing application where building the backend specifically dedicated to the UI won’t be beneficial. It provides a variety of benefits: standardized responses, ability to rearrange calls on backend without touching frontend, adding app-specific security logic etc.

Imagine now that the frontend is displaying the information collected by its BFF from multiple sources. Another user-facing application wants to display similar information and requests some of the BFF’s APIs to be reused. This should be avoided: the BFF APIs are optimized for the specific app (some calls can be merged/split for performance, service may not handle the combined load etc.). Using same endpoints from another user-facing application will block the original application to optimize them further.

Human nature and organizational challenges

Taking away technical details of implementing the aggregation service, the human nature adds 2 strong centers of gravity that will drive the design of components of a system:

- using the data

- storing the data

The evolution of system design then tends to keep the systems that face the final users (using the data) and systems that store the data. The intermediate layers tend to be very fluid. They can easily lack support and resources unless they’re artificially reinforced by few levels of leadership. Keeping these layers stable isn’t only a technical but also an organizational challenge.

Organizational challenge is hard to quantify: how much firmness do you add into your org so that it maintains the organizational structure and also that it doesn’t become a dictatorship? Making it too firm can block the creativity of the teams, and keeping it loose can make the system architecture so unstable that it will drain resources to keep it running.

Being a lead (architect, manager, director) requires hearing the feedback, placing the limits of pursuing certain goals and allowing certain level of chaos in your organization. Controlling this chaos and allowing different levels of it in different situations is essentially the art of leadership (it’s a good topic for another post).

Another related thought: the architectural choices that are based on conventions - like for instance a convention of what aggregation strategy to choose - will eventually erode. As I mentioned, they need to be reinforced by few levels of leadership to stay longer. Few things will make them more solid:

- documenting the conventions

- wide adoption

- know your use cases and keep aggregation layers close to where they are used

- keep contact with people (clients and sources) - even though the aggregator is the technical solution, it will be people who will decide whether to use it or not

- platform approach

- add value on top of just aggregating data: where to find data, how to keep contracts updated, whom to contact in case of failures

- provide information about system as a whole: corelated failures, execution plan for aggregation routes, info on cross-datacenter connections for aggregation routes etc

- provide services and automation that would otherwise be client requirements: notification of failures, performance tests, resiliency measures (rate limiting, retries, bulkheads)